Euripides’ departure from Athens in his old age has been attributed to the playwright’s disappointment with the hostility that greeted his works.

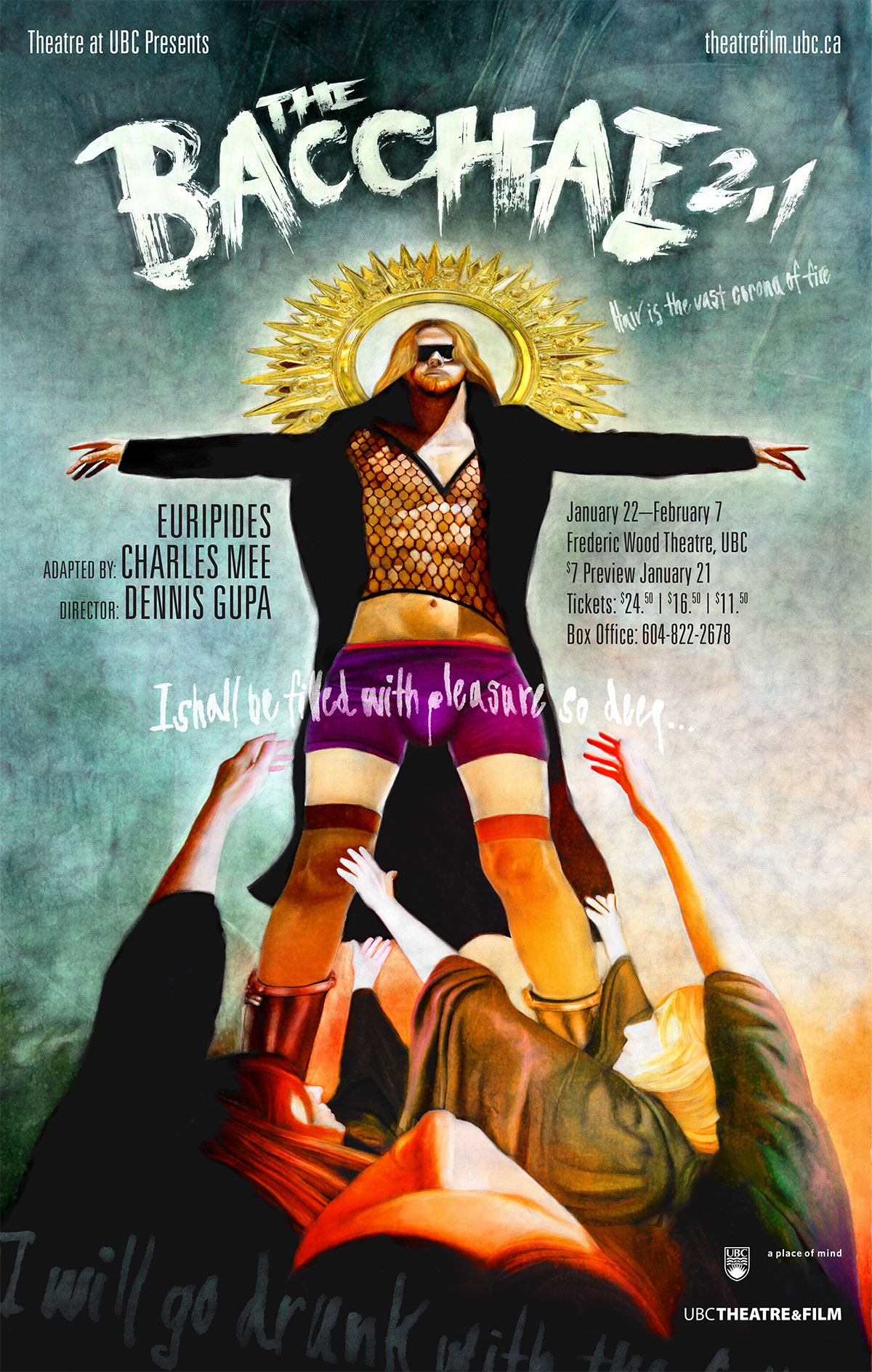

In 408 Euripides left Athens at the invitation of the Macedonian king Archelaus, who hoped to establish a cultural center to rival Athens. Michael Walton has observed that “The sheer power and mystery of the Bacchae is so startling that it rightly belongs in the forefront of the greatest plays ever written.” The Bacchae persists largely because of the play’s astonishing capacity to harness psychological and emotional forces to form a central myth with far-reaching psychological, moral, and ontological implications.Īs the Peloponnesian War (431–404 b.c.) ground on toward Athens’s eventual defeat, Euripides completed a series of tragedies- Electra (413), Phoenician Women (409), and Orestes (408)-reflecting the playwright’s bitterness and growing despair.

And, whether it was intended to encourage or to discourage fanaticism, the picture of fanatical excitement which it exhibits has never been rivaled.” Critic J. But, as a piece of language, it is hardly equaled in the world. It is often very obscure and I am not sure that I understand its general scope. “The Bacchae,” poet and historian Thomas Macaulay wrote “is a glorious play. The violent natural forces Dionysus embodied are treated as both essential and terrifyingly destructive with Dionysus and his resister, Pentheus, presented in ways that raise as many questions as consolations. It has been interpreted as both Euripides’ approval of Dionysian nature worship and his condemnation of its excesses. The only Greek drama to feature the god Dionysus as a central character, the Bacchae is a drama about belief and faith, expressed with Euripides’ characteristic willingness to complicate easy answers. A play of great poetry and suggestiveness, the Bacchae is in many ways Euripides’ most provocative work.

Written in Macedonia after the playwright’s voluntary exile from Athens, the Bacchae was produced after Euripides’ death around 406 b.c. John Davie, Preface to Bacchae, in The Bacchae and Other PlaysĮuripides’ Bacchae claims a preeminent place in both classical Greek drama and Euripides’ career as his and his age’s last great tragic drama. The difference is that the god lacks the dramatist’s compassion.

In one key scene Dionysus asks the question which has perplexed theorists of tragedy: “would you really like to see what gives you pain?” Dionysus, ironic questioner and stage-manager of the action, is a double of the poet himself.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)